Well, perhaps not ‘everyone’s’ talking about reciprocity…

But on Saturday evening, I joined my fellow film photographers from the Melbourne Silver Mine Inc. to be part of a commission from the White Night festival (an all night long event that only half a million folks wandered into the city to see) to document the event from two superb vantage points – the top balcony of Hamer Hall, and the first floor of Transport Hotel – two great views of the Princes Bridge and environs.

The photographic challenge of course, is shooting the city at night – and how to do that, with film, on a large format camera. Specifically, how long to expose the film? Metering of course, but… the exposures will be LONG (Large Format lenses are ‘slow’ – that is, they have small maximum apertures and don’t let in a lot of light), and film goes a bit ‘funny’ when you expose it for longer times than normal.

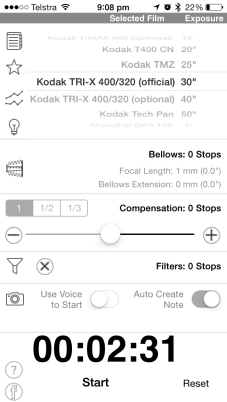

This funny behaviour is called reciprocity – and means different types of film start requiring more (and different) amounts of exposure when the times get longer than a few seconds. In the old days, you could puzzle over this with formulae, or by studying the behavioural graphs from the product data sheets provided by each manufacturer for their films, but now, of course, there’s an app (several in fact).

So I set up my trusty 5×4″ field camera, and used a spot meter to make a series of light readings of the highlights and shadows in the frame that I wanted to end up on film, then pressed the magical ‘average’ button to get an mid-tone exposure for the film (in this case, Kodak TXP320, which I expose at ISO200). In daytime, that’s normally all I’d do, then I’d pick an aperture/shutter speed pair accordingly. But for these pictures I then used an app to ‘correct’ the exposure for the reciprocity characteristics of Kodak TXP320.

This means what was metered as f/22 for 30 seconds, becomes f/22 for 2 minutes and 31 seconds. Quite a difference – but it matters, because otherwise the film is underexposed. It’s all a bit of a nuisance, but the proof is in the pudding (or the developing tank, or something).

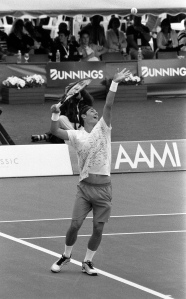

And then, with a steady tripod, and everything on the camera locked down tightly – the resulting snap is a treat, with the unlikely mass of people on the bridge blurred to a ghostly fog (except for select dawdlers), but the bridge and background architecture sharp and immobile (as it should be). Hurrah!